( of )

Correct: 0

Incorrect: 0

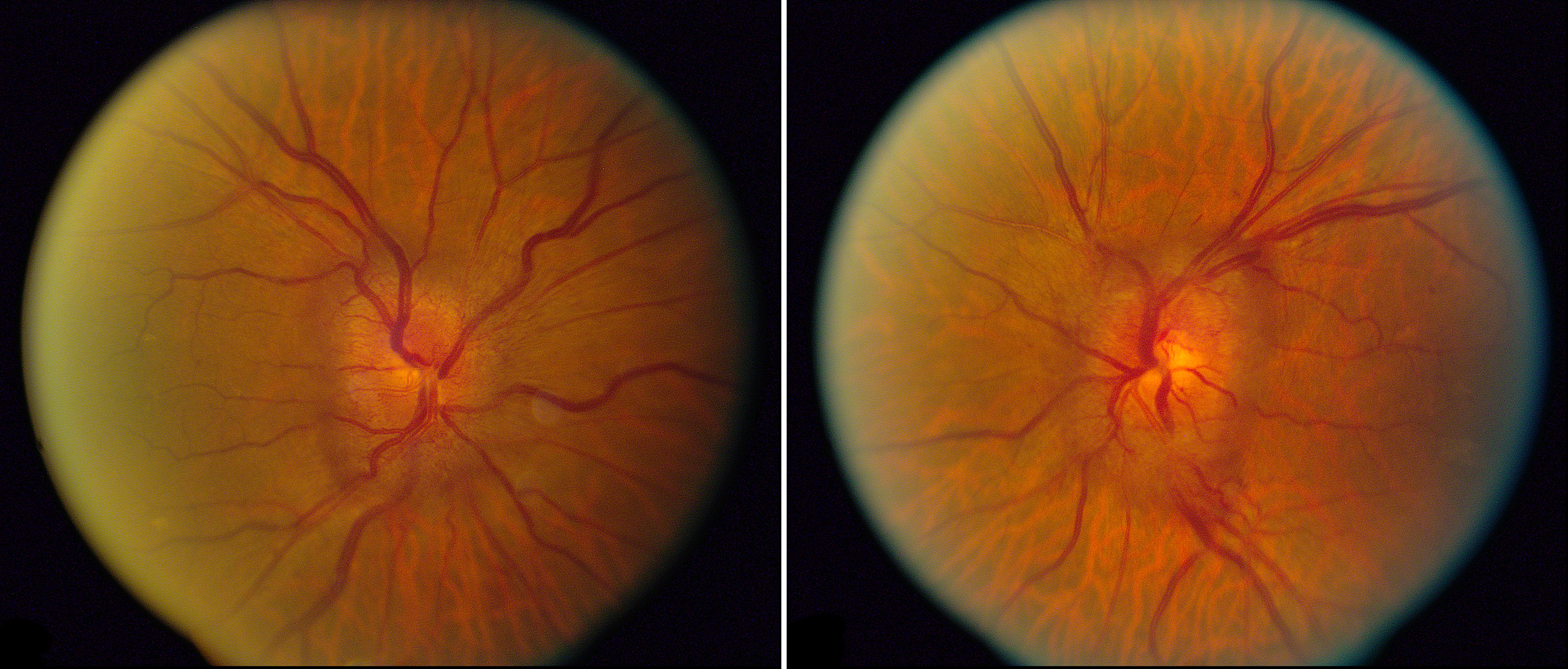

A 48 year old overweight woman is found on optometric examination to have the optic fundus appearance you see here. She suffers from moderate episodic headaches that have elicited a diagnosis of migraine. She has no visual symptoms. She was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus 2 years ago and blood sugar is well-controlled on a single oral agent. Visual acuities are normal and visual fields show very mild inferior arcuate nerve fiber bundle defects. Autofluorescence is normal. Fluorescein angiography shows mild optic disc staining. Optical coherence tomography confirms bilateral optic disc and slight peripapillary retinal elevation.

What diagnosis do you make?

Correct!

This is a difficult diagnosis to make. First, decide if the bilateral optic disc elevation is congenital or acquired—not always easy on ophthalmoscopy alone.

Preservation of the physiologic cup with elevation and obscuration of the peripapillary nerve fiber layer are clues to acquired optic disc elevation; so are

papillary or peripapillary hemorrhages. Second, decide among various causes of acquired bilateral optic disc elevation, which conveniently start with the letter

“i:” inflammation, ischemia, increased intracranial pressure (papilledema), increased systemic blood pressure (hypertensive optic disc edema), increased retinal

venous pressure (retinal vein occlusion), inherited disorders (Leber hereditary optic neuropathy), intoxications (toxic optic neuropathy), intolerance to glucose

(diabetes mellitus), and insidious vitreous traction on the optic disc.

Inflammatory optic disc elevation usually causes leakage on fluorescein angiography; so does papilledema, although minimally.

The preservation of visual acuity largely excludes LHON and intoxication; it does not entirely exclude ischemic optic neuropathy, which often spares the maculopapillar axons, but simultaneous binocular occurrence is unusual in that condition.

Central retinal vein occlusion can cause considerable optic disc elevation, but engorged retinal veins and perivenous hemorrhages should also be present. Hypertensive optic disc edema is often binocular, but signs of retinal arterial occlusive disease should be evident. Vitreous traction syndrome would have to be established with OCT. It usually does not impair optic nerve function and cannot be invoked without ruling out papilledema.

Therefore, you must order brain imaging here. If it is negative, lumbar puncture will be next. If brain imaging and lumbar puncture are negative, you could fall back on a diagnosis of diabetic papillopathy. Whether diabetic papillopathy is a mild but lingering form of non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy has not been resolved.

I always forget to include Wernicke encephalopathy on the list of causes of binocular optic disc edema. This condition is mostly known for its famous triad—confusional state, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia (also nystagmus)—but Wernicke’s three original cases all had optic disc edema. So keep it in mind even when one or more components of the famous triad is not present!

Inflammatory optic disc elevation usually causes leakage on fluorescein angiography; so does papilledema, although minimally.

The preservation of visual acuity largely excludes LHON and intoxication; it does not entirely exclude ischemic optic neuropathy, which often spares the maculopapillar axons, but simultaneous binocular occurrence is unusual in that condition.

Central retinal vein occlusion can cause considerable optic disc elevation, but engorged retinal veins and perivenous hemorrhages should also be present. Hypertensive optic disc edema is often binocular, but signs of retinal arterial occlusive disease should be evident. Vitreous traction syndrome would have to be established with OCT. It usually does not impair optic nerve function and cannot be invoked without ruling out papilledema.

Therefore, you must order brain imaging here. If it is negative, lumbar puncture will be next. If brain imaging and lumbar puncture are negative, you could fall back on a diagnosis of diabetic papillopathy. Whether diabetic papillopathy is a mild but lingering form of non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy has not been resolved.

I always forget to include Wernicke encephalopathy on the list of causes of binocular optic disc edema. This condition is mostly known for its famous triad—confusional state, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia (also nystagmus)—but Wernicke’s three original cases all had optic disc edema. So keep it in mind even when one or more components of the famous triad is not present!

Incorrect

Incorrect