( of )

Correct: 0

Incorrect: 0

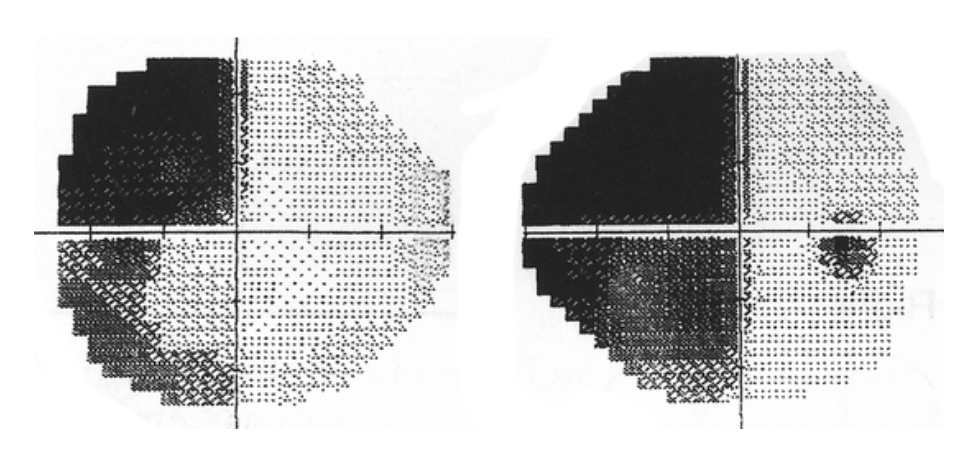

A 29 year old woman noticed a defect in the vision of “my left eye” of uncertain duration. Optometric and ophthalmologic examinations were negative. The patient sought care from a neurologist for numbness in the legs, but the examination was normal. Because the vision defect persisted, the patient returned to the optometrist, who now performed a formal visual field examination that yielded this result.

Where is the lesion?

Incorrect

Correct!

These visual field defects are confined to the left hemifields in both eyes and they have borders aligned to the vertical meridian, defining them as an

incomplete “homonymous hemianopia.” But notice also that the defects in the two eyes are not of the same extent. If you overlaid them, they would not

superimpose. This difference in the size of the two defects is called “incongruity.” If that incongruity is a true representation—and not simply an

inconsistency in patient performance on the test—then the lesion must lie in the optic tract, where axons from corresponding points in the retinas of the

two eyes have not yet come to lie close to one another.

These visual field defects are confined to the left hemifields in both eyes and they have borders aligned to the vertical meridian, defining them as an

incomplete “homonymous hemianopia.” But notice also that the defects in the two eyes are not of the same extent. If you overlaid them, they would not

superimpose. This difference in the size of the two defects is called “incongruity.” If that incongruity is a true representation—and not simply an

inconsistency in patient performance on the test—then the lesion must lie in the optic tract, where axons from corresponding points in the retinas of the

two eyes have not yet come to lie close to one another.

After all, the optic tract lies early in the retrochiasmal portion of the visual pathway, which carries out the transformation of visual representation in the brain from monocular to hemifield. As the axons proceed farther posteriorly, through the lateral geniculate bodies and optic radiations to visual cortex, axons from corresponding retinal points become neighbors, so that incomplete homonymous hemianopias become more congruous.

The optic tract is wedged between the temporal lobe and the midbrain/hypothalamus.

Crammed into this tight space, it becomes contused and atrophied as the temporal lobe swells.

Tip: because there is very little CSF in this tight space to set off the optic tract, a lesion is difficult to visualize on MRI, as you

can see here. It is often overlooked unless you direct the radiologist’s attention to this area!

After all, the optic tract lies early in the retrochiasmal portion of the visual pathway, which carries out the transformation of visual representation in the brain from monocular to hemifield. As the axons proceed farther posteriorly, through the lateral geniculate bodies and optic radiations to visual cortex, axons from corresponding retinal points become neighbors, so that incomplete homonymous hemianopias become more congruous.

The optic tract is wedged between the temporal lobe and the midbrain/hypothalamus.

Incorrect

Incorrect