( of )

Correct: 0

Incorrect: 0

A 65 year old woman had a cardiac arrest with brief loss of consciousness. When she regained full consciousness, she began to complain that “my vision is just not normal.” Yet visual acuity was normal and there were no abnormalities of eye movements or alignment. Visual fields were full to finger displays. The neurologic examination was normal except that her walking was tentative. She had difficulty when asked to pick objects out of an array, as demonstrated in this video

Where is the lesion?

Incorrect

Incorrect

Correct!

This patient is unable to point accurately to objects in an array. Also, she forgets which ones she has already identified, so she miscounts. Her deficits

are visuospatial and attentional. The misreaching is called “optic ataxia.” It is best elicited by comparing the accuracy of reaching for objects in

extrapersonal space (inaccurate) and touching parts of the patient’s own body (accurate).

This patient is unable to point accurately to objects in an array. Also, she forgets which ones she has already identified, so she miscounts. Her deficits

are visuospatial and attentional. The misreaching is called “optic ataxia.” It is best elicited by comparing the accuracy of reaching for objects in

extrapersonal space (inaccurate) and touching parts of the patient’s own body (accurate).

Apart from misreaching, there is another important deficit here. The patient can identify individual objects, but she cannot aggregate them or understand the relationships that these objects have to each other. The term “simultanagnosia” has been applied to this phenomenon. Although some observers have called this “searchlight vision,” that description is incorrect. Patients with markedly constricted visual fields that preserve acuity (for example, advanced glaucoma) may see only one object of an array at a time, but after scanning, they will have no difficulty aggregating the elements so that they can interpret the whole picture.

A useful way to bring out simultanagnosia is to present the patient with a picture that has different elements (a magazine page, for example) and ask the patient to describe what is there. The patient will fixate on one object and be unable to see how it relates. Shown a picture of a baseball, the patient might fixate on the seams and call it “railroad tracks.”

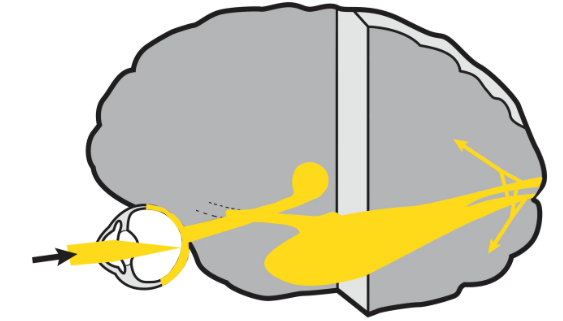

The lesions lie in the inferior parietal lobules on both sides, interrupting the integration of visual and somatosensory information and the application of attention appropriate to the task. Called Balint syndrome, or Balint-Holmes syndrome, it most often arises acutely from biparietal stroke, usually in the setting of systemic hypotension (“watershed” or “border zone” infarction).

When these deficits appear chronically, the most common cause is the “visual variant” of Alzheimer disease, sometimes known as “posterior cortical atrophy.”

The third deficit in Balint-Holmes syndrome—not shown here--is an inability to generate volitional gaze, attributed to lesions in the inferior parietal lobules bilaterally. Non-volitional gaze, mediated by the vestibulo-ocular reflex, is intact. Although his deficit is sometimes called “ocular motor apraxia,” it is more properly called a “supranuclear gaze disturbance.”

Here is something else you should know. The aging brain, and the brain with even minimal dementia, has trouble with “divided attention.” How does this manifest? As difficulty switching concentration from a viewed object to an object elsewhere in the environment. This problem becomes particularly dangerous in driving. Older drivers, and those with dementia, are often attentionally “consumed” by stimuli directly in front of them and will not react to stimuli in the field periphery, a phenomenon sometimes known as “spasm of fixation” or the “visual grasp reflex.” It reduces the “useful field of view.” This deficit probably relates to a decline in biparietal function. As a cause of driving accidents (cars, bicycles), it is more important than moderately impaired visual acuity or even visual field. Yet no driving test assesses it! Go figure.

Apart from misreaching, there is another important deficit here. The patient can identify individual objects, but she cannot aggregate them or understand the relationships that these objects have to each other. The term “simultanagnosia” has been applied to this phenomenon. Although some observers have called this “searchlight vision,” that description is incorrect. Patients with markedly constricted visual fields that preserve acuity (for example, advanced glaucoma) may see only one object of an array at a time, but after scanning, they will have no difficulty aggregating the elements so that they can interpret the whole picture.

A useful way to bring out simultanagnosia is to present the patient with a picture that has different elements (a magazine page, for example) and ask the patient to describe what is there. The patient will fixate on one object and be unable to see how it relates. Shown a picture of a baseball, the patient might fixate on the seams and call it “railroad tracks.”

The lesions lie in the inferior parietal lobules on both sides, interrupting the integration of visual and somatosensory information and the application of attention appropriate to the task. Called Balint syndrome, or Balint-Holmes syndrome, it most often arises acutely from biparietal stroke, usually in the setting of systemic hypotension (“watershed” or “border zone” infarction).

The third deficit in Balint-Holmes syndrome—not shown here--is an inability to generate volitional gaze, attributed to lesions in the inferior parietal lobules bilaterally. Non-volitional gaze, mediated by the vestibulo-ocular reflex, is intact. Although his deficit is sometimes called “ocular motor apraxia,” it is more properly called a “supranuclear gaze disturbance.”

Here is something else you should know. The aging brain, and the brain with even minimal dementia, has trouble with “divided attention.” How does this manifest? As difficulty switching concentration from a viewed object to an object elsewhere in the environment. This problem becomes particularly dangerous in driving. Older drivers, and those with dementia, are often attentionally “consumed” by stimuli directly in front of them and will not react to stimuli in the field periphery, a phenomenon sometimes known as “spasm of fixation” or the “visual grasp reflex.” It reduces the “useful field of view.” This deficit probably relates to a decline in biparietal function. As a cause of driving accidents (cars, bicycles), it is more important than moderately impaired visual acuity or even visual field. Yet no driving test assesses it! Go figure.

Incorrect